We Don't Talk About "Crazy" in Russia

When I was seventeen, my friend told me about his experience in a "yellow house"—the slang term for public psychiatric hospitals in Russia. Because I did not want to lose my friend—and I was convinced that I absolutely would the second he admits to his experience—I wanted him to stay quiet.

When I was seventeen, my friend told me about his experience in a "yellow house"—the slang term for public psychiatric hospitals in Russia.

I really don't remember his story that well because during that conversation, I just couldn't get over the fact that I was talking to a real crazy person.

And it wasn't his story that established him as such in my mind, but the fact that he was telling it.

I mean, it is one thing to end up in an institution—supposedly, because, when you watch a movie, certain combinations of pictures and sounds make you weep uncontrollably—but quite another is to go around talking about it.

I thought him confessing to me was the most outrageous act I ever saw performed in public: he could have been a serial killer acting on behalf of the devil, I would not think him more out of his mind.

You think I'm Crazier Than You

When Katerina P. writes, "being mental (with a confirmed diagnosis) is not a high status on the scale of popularity in our society," she only repeats what we all know already—stigma exists.

She views the "confirmed diagnosis" as a socially accepted way of determining the level of normality of an individual.

However, even a confirmed diagnosis is not based on objective, measurable, concrete and absolute methods.

"Symptoms do not speak for themselves," so the diagnosis is always somewhere at the intersection of the level of social conformity of a patient and the subjectivity of a psych-specialist, as we begin to see in Blackman's book.

So, even with a confirmed diagnosis, one can hope for a terrible mistake, which has jeopardized one's image of being non-crazy normal.

And I desperately wanted my friend to cling to this possibility.

Because we, Russians, were supposed to be tough and resilient, we had no right to go crazy.

Because crazy people in Russian were considered only half people (and half caged animals, perhaps), we had no right for weakness.

Because I did not want to lose my friend—and I was absolutely convinced that I would the second he admits to his experience—I wanted him to stay quiet.

What I did not realize back then was that the border between normal and crazy is ever-so-blurred.

I did not realize back then that him accepting himself in front of me was not a sign of weakness at all.

What I also did not know back then was that being normal and yourself is often at odds.

Now, I wish I was better equipped at seventeen to reply to this enormous gift of trust with more empathy and compassion. I wish I had words to communicate acceptance and love back then.

Now, more realistically, I hope I will be able to transmit acceptance through my words in this blog.

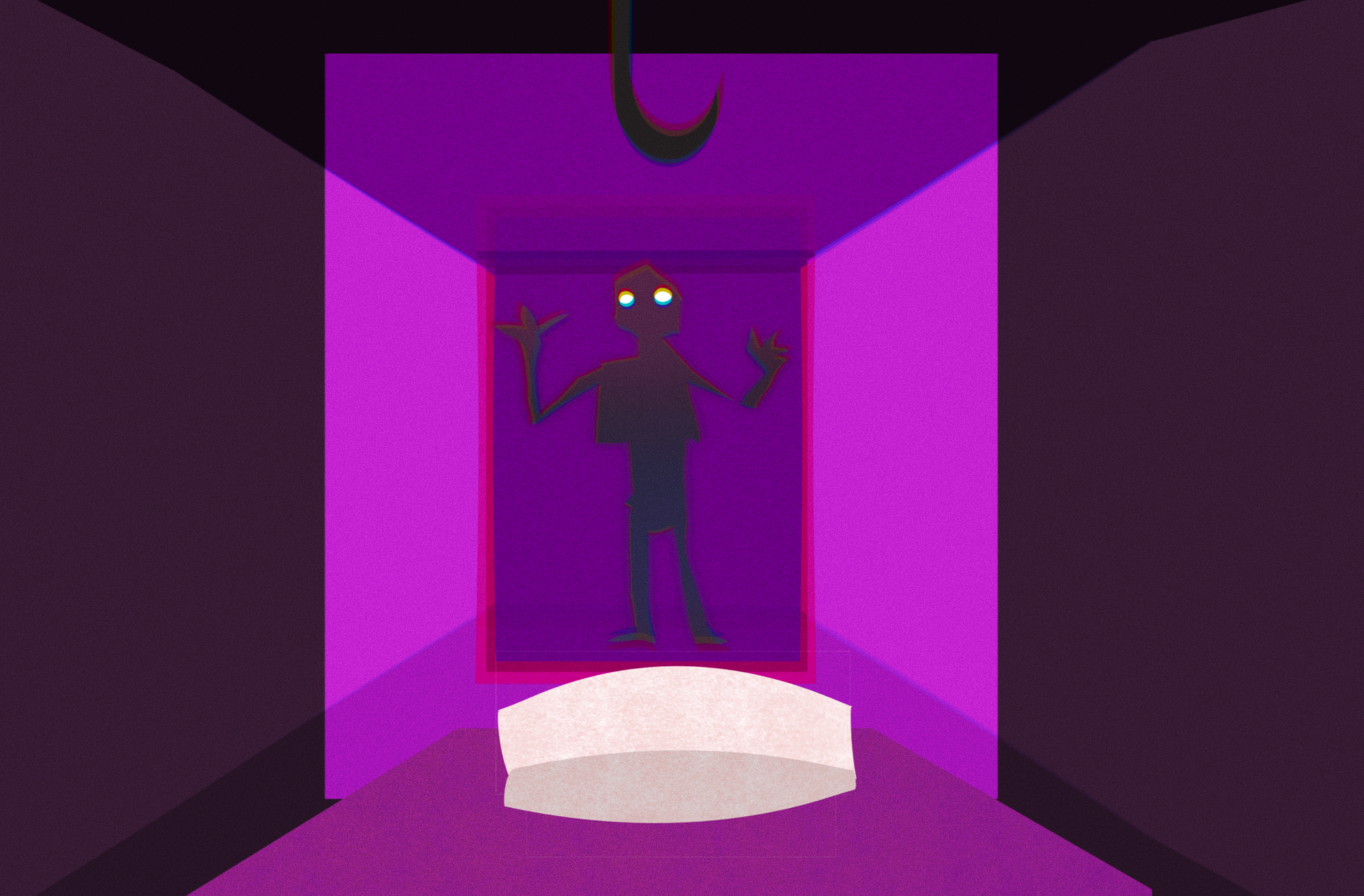

Hook and Help

My friend said there was a metal hook above his bed.

He said that he had to give his shoelaces away.

He said he could not stop thinking about the hook and the laces,

"So pointless... Why have a hook on the ceiling at all if laces are not available?"

My friend said he felt lonely in that bed. My friend said he had been lonely ever since.

And that's when I realized that we were more alike than different.

If you strip off labels, both of us were only human.

And just being there to validate his experience as real–and who cares how normal it was–just being a witness to his struggle was help.

So I did not talk to him about crazy. I listened.